Ridley Scott's Lost Dune: Unveiling a 40-Year-Old Secret

This week marks four decades since David Lynch's Dune premiered, a box office flop that later cultivated a devoted cult following. Its stark contrast to Denis Villeneuve's recent adaptations of Frank Herbert's novel has fueled renewed interest in the project's history. This article delves into a previously unknown chapter: Ridley Scott's abandoned Dune adaptation.

Thanks to T.D. Nguyen's discovery within the Coleman Luck archives, a 133-page October 1980 draft of Scott's script, penned by Rudy Wurlitzer, has surfaced. This draft, intended as part one of a two-part series, reveals a significantly different vision than either Lynch's or Villeneuve's interpretations.

Scott, fresh off the success of Alien, inherited Frank Herbert's already-existing, unwieldy screenplay. He selected a handful of scenes but ultimately commissioned Wurlitzer for a complete rewrite. Wurlitzer himself described the process as incredibly challenging, stating that structuring the narrative consumed more time than writing the final script. He aimed to capture the book's essence while infusing a unique sensibility. Scott later confirmed the script's quality, calling it "pretty fucking good."

Several factors contributed to the project's demise: the death of Scott's brother, his reluctance to film in Mexico (De Laurentiis's demand), a ballooning budget exceeding $50 million, and the perceived viability of Filmways' Blade Runner project. However, a key factor, as revealed in A Masterpiece in Disarray – David Lynch's Dune, was the script's failure to garner universal acclaim.

This article presents a detailed analysis of Wurlitzer's script, allowing readers to judge its cinematic merits and assess whether its darker, more violent, and politically charged narrative proved too risky for a studio blockbuster. While Wurlitzer and Scott declined to comment, the script itself speaks volumes.

A Different Paul Atreides

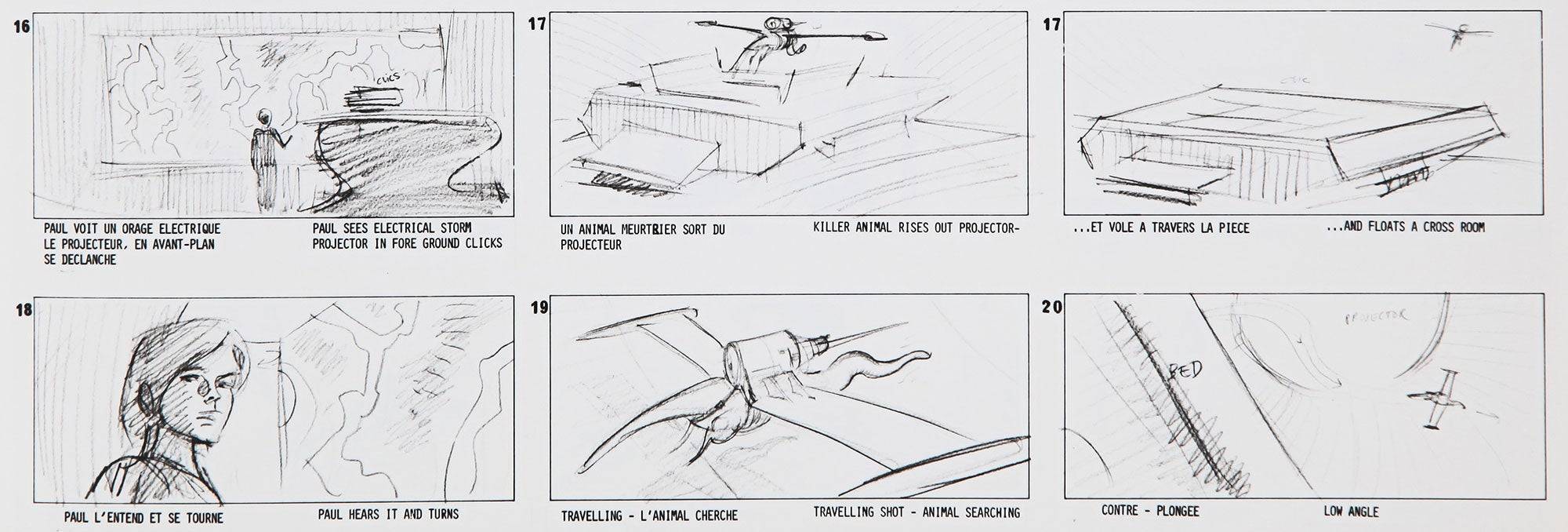

The script opens with a dream sequence depicting apocalyptic armies, foreshadowing Paul's destiny. Scott's signature visual density is evident in descriptions of whirling birds and insects. Instead of Timothée Chalamet's portrayal, Paul is depicted as a 7-year-old, undergoing trials that showcase his psychic abilities and ruthless determination. This young Paul displays a "savage innocence," actively taking charge and demonstrating a relentless drive to surpass even Duncan Idaho. This contrasts with Lynch's portrayal, which emphasized Paul's vulnerability.

The Emperor's Death and Political Intrigue

A pivotal twist involves the Emperor's death, a catalyst not present in the book. The revelation unfolds during a poignant scene featuring Jessica observing a gardener, culminating in the gardener's proclamation of the Emperor's demise. This sets the stage for the gathering of the Great Houses and the subsequent events. The Baron Harkonnen's dialogue echoes a famous line from Lynch's film, highlighting the importance of spice control.

The Guild Navigator and Arrakis

The script features a detailed depiction of the Guild Navigator, a spice-mutated creature visualized as an elongated, humanoid figure. The Navigator's actions, involving the ingestion of a pill and the emission of musical intonations to "Engineers," hint at Scott's later work, Prometheus. The arrival on Arrakis showcases Scott's medieval aesthetic, with descriptions of the Atreides fortress and the ecological impact of spice harvesting. The flight through the desert, culminating in a worm attack, mirrors the hellish cityscapes of Blade Runner.

The script also introduces a new scene: a bar fight in Arakeen, showcasing Paul and Duncan's combat skills. This scene, while adding action, potentially undermines Paul's character development. Their encounter with Stilgar and the subsequent decapitation of a Harkonnen agent further highlight the script's violent tone.

Jessica's Revelation and the Deep Desert

The script includes a scene where Jessica and the Duke consummate their relationship, explicitly described. Paul's journey into the deep desert is depicted with intense detail, emphasizing the physical challenges and the sensory overload. The crash landing, the struggle for survival, and the encounter with a massive sandworm mirror elements found in Villeneuve's adaptation.

The script notably omits the mother-son incestuous relationship present in earlier drafts, a change that reportedly angered Herbert and De Laurentiis. While this element is absent, a scene where Paul and Jessica lie together on a sand dune remains.

The encounter with the Fremen, the duel with Jamis, and the subsequent integration into the tribe are vividly described. The Water of Life ceremony, featuring a Shaman with three breasts and a sandworm, adds a surreal and mystical element. The script concludes with Paul and Jessica's acceptance by the Fremen, setting the stage for future conflicts.

A Bold, Controversial Vision

This script, while deviating significantly from Herbert's source material, offers a unique interpretation of Dune, emphasizing its ecological, political, and spiritual dimensions. Its darker, more violent, and adult themes likely contributed to its rejection. The script's focus on Paul's ruthless ambition and the complicity of other characters presents a more complex and morally ambiguous narrative.

The script's legacy includes H.R. Giger's designs and the involvement of Vittorio Storaro. While it never reached the screen, it offers a fascinating glimpse into what could have been, a vision of Dune that prioritized ecological concerns and political intrigue alongside its science fiction elements. The script's enduring relevance lies in its exploration of themes that remain powerfully resonant today. The article concludes by suggesting that future adaptations might benefit from revisiting the ecological underpinnings of Herbert's work.